Artist essay on the performance art piece “Dance of the Elephant / The Spirits’ Revenge” (2022).

I initiated into the secrets of La Regla de Ocha amidst the lingering odors of an uprising and pandemic. The air was/ is stale with perspiring fear and embers of anger, probably hauling us all towards madness reminiscent of epochs constructed as “past”. I came to Ocha looking for peace. Healing is what I found. Past made present, present as future, future as past, all as now.

African/diasporic and global Indigenous epistemologies trouble Eurocentric linear temporality and offer us “an alternative model of time” (Dodson 2008, 2). This is presented to us via healing practices and outcomes as well as sacred religious ceremonies that invoke ancestors or the so-called “dead”. ‘Past’ and ‘future’ collapse into a ‘present’, illustrating the fluidity of these categories, impacting the ways in which we define our experiences and what we believe to be ‘known.’ For Tehching Hsieh, the performance artist known for his durational work, “art exists by itself and has its own life. When time has passed, only art documents stay as a trace for the work to remain” (Heathfield and Hsieh 2009, 327).

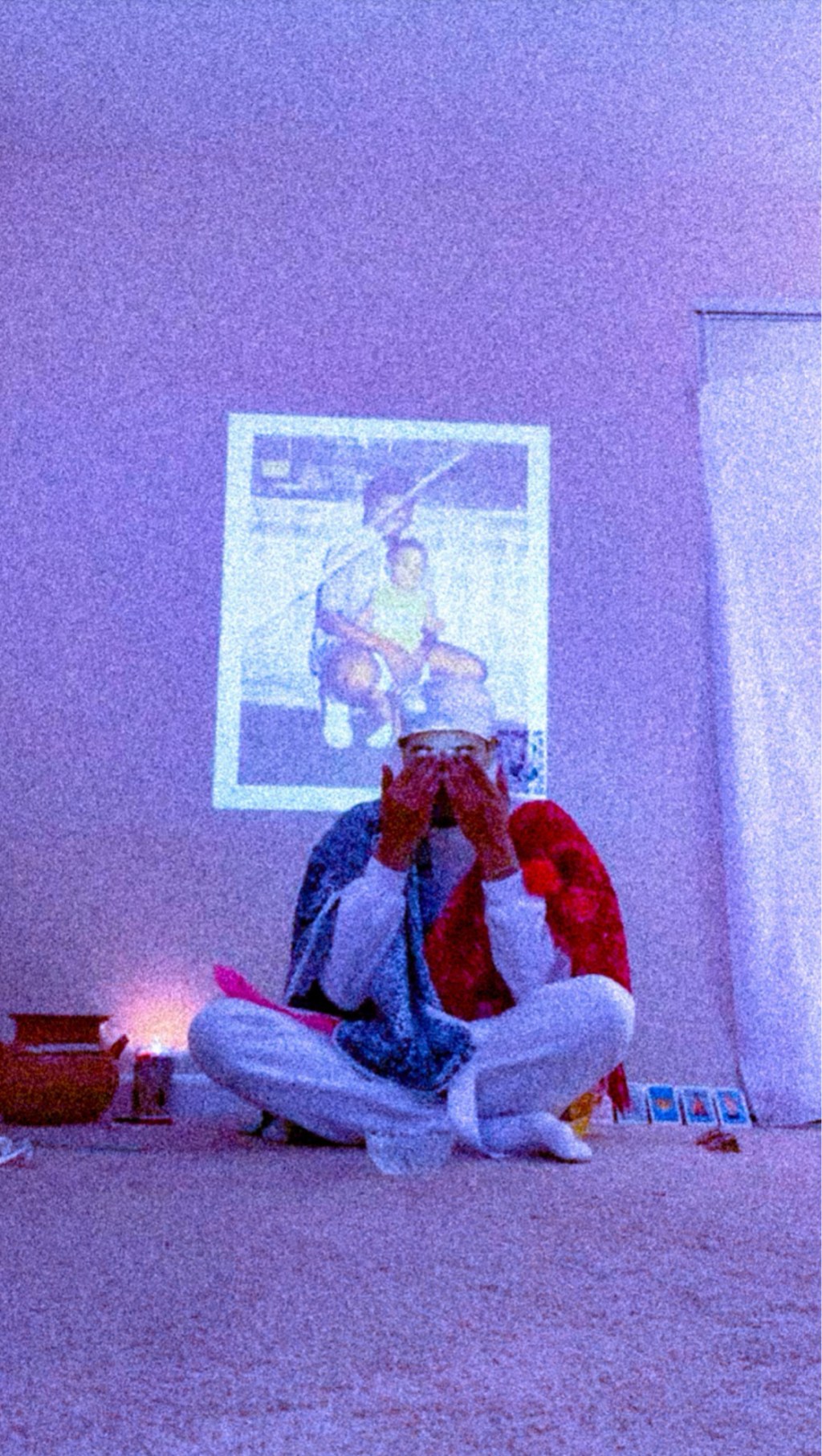

This temporal collapse through initiation, performance art, or ritual does not clone a cohesive past into the present or creates a clear image of the future, but develops traces or residues of both into the now. I sought to introduce this via the projected image of my child self and mother at the backdrop of my artistic rendition of initiation and sacred ritual and the re-projection of these filmed acts to a live audience while conducting another, connected performance.

While not an explicitly political performance, as Hsieh states, “it is my reality that compels me to confront political issues” (Heathfield and Hsieh 2009, 330). It would be insincere to erase the political dimensions of Afro/ Indigenous religious expression or of deeply personalized healing processes. Ancestral knowledges cannot exist without ancestors, all of whom were people deeply ingrained in their (political) contexts, as well as acting as their protagonists and reproducers.

My performance sought to collapse the temporality of making Ocha, both as a reference to its mechanics and ethos as well as to facilitate its comprehensibility to audiences negotiating varying layers of fear, acceptance, curiosity, and hatred for Afro/ Indigenous religions.

In an interview on his work engaging time and life, Tehching Hsieh said, “when dealing with memories the biggest matter is not about their accuracy. Rather, it is about how to manage and rearrange these fragments of memories, transfer them into language and a process of discourse” (Heathfield and Hsieh 2009, 330). Secrecy and openness can accomplish the same outcomes, whether increased intolerance or entrenched abjection.

According to art scholar Jennifer A. González, James Luna’s conceptual and performance art practices exemplify what she cites as Homi Bhabha’s theory of hybridity, centering historically unequal power dynamics in the conversations of cultural exchange, subverting normalized notions of acceptability and legibility or “rules of recognition.” (2011, 30). Luna’s work with the semiosis of sacred indigenous traditions introduces “unfamiliar signs or denied knowledges… undecipherable for some viewers…” (2011, 30).

My performance was an invitation and provocation, because there’s also power reclamation in illegibility. I also believe that “taking the Sacred seriously would propel us to take the lives of primarily working-class women and men seriously, and it would move us away from theorizing primarily from the point of marginalization” (Alexander 2005, 328). In a society and world deeply defined by conflict and suffering, this is an essential task.

The intent behind the performance was also to clear the way for these complex, intense emotions and reactions to these religions. This/ we exist, whether you like to or not. In the shadows is not where I choose to live. Maybe I / we may (re)see something by that. For William Pope.L, whose work draws our attention to bodily racializations and religious resignification, “art re-ritualizes the everyday to reveal something fresh about our lives” (Murray 2010, 25). We are all involved in ritual performances or performances maintained by ritual, crossing into thresholds we knew must be made to fulfill life’s journey, sometimes with delay or avoidance, embrace and/ or rejection.

Also known as Afro-Cuban Lucumí or Santería, La Regla de Ocha demands durational endurance across all stages of devotion and initiation. It took years to manifest these events into existence; a filtering of emotions and perspectives embodied in a series of choices that includes bodily labor. Sacred ceremonies with multi-generational expertise costs money. Choosing tutelage under a secretive society of priests takes discernment and patience. Being chosen by the Orisha for initiation requires faith. Making mistakes is integral to the process. Initiation or “making Ocha” is seven days long, with a (semi) public third day, and then a year-and-seven-days of a very public performance of fidelity and status as a new initiate or iyawo, with the most recognizable display being the wearing of all white clothes. For a select few of initiates, this will be a life-long uniform.

Discussing the “Rope Piece”, Hsieh “Privacy also contains darkness, which we sometimes do not want to confront” (Heathfield and Hsieh 2009, 336). Contrary to popular(ized) belief, initiation into the secrets of La Regla de Ocha are not a panacea to life’s woes or induction into a coven of witches. It is about elevation byway of healing, which is a confrontation of oneself and an acceptance of life’s reflective beauty and disfigurements. There is still work to be done after initiation. Personal and collective issues to address. Ocha insists on this. The Spirits demand this.

I washed my face in a glass bowl of water at the performance’s finality. The visuality of water seemed to be an ideal format because of its universality. Everyone needs water for survival and encounters it in one form or another. With this being said, there is a saliency and sanctity of water to historically oppressed communities that is individually and collectively felt. For Afro/ Indigenous communities around the world, water is an abode for divinities (or Orisha in La Regla de Ocha) that must be approached with humility. Some of these entities may or may not be gendered and even provide special protection to queer peoples. This is to say: we can all partake in the sanctity of water and the queer, if we allow ourselves to, if we are humble enough. As the performance scholar José Esteban Muñoz aptly stated, “a focus on affect potentially denaturalizes experiences like racism or homophobia. We are all weighed down, burdened, by emotions that are radiated toward us. And we all seek relief” (Muñoz 2006, 194).

Works Cited:

-

Alexander, Jacqui M. Pedagogies of Crossing: Meditations on Feminism, Sexual Politics, Memory, and the Sacred. (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2005).

-

Dodson, Jualynne E. Sacred Spaces and Religious Traditions in Oriente Cuba. (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 2008).

-

González, Jennifer A. Subject In Display: Reframing Race in Contemporary Installation Art. (Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2011).

-

Heathfield, Adrian and Hsieh, Tehching. Out of Now: The Lifeworks of Tehching Hsieh. (The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, 2009).

-

José Esteban Muñoz, “The Vulnerability Artist: Nao Bustamante And the Sad Beauty of Reparation”, Women & Performance: a journal of feminist theory, 16 no. 2 (2006): 191-200.

-

Murray, Derek Conrad and Murray, Soraya. “Public Ritual: William Pope.L and exorcisms of abject otherness”, Public Art Review, 22 no. 1 (Fall/ Winter 2010): 24-27.